Fourteen-year-old Ahmed Mohamed was arrested on Monday after he brought a clock he made at home to school to show his science teacher. After another teacher saw the clock and suspected it was a bomb, he was interrogated for more than an hour by five police officers, then handcuffed and taken to the police station in his home town of Irving, Texas. His arrest sparked outrage against Islamophobia and a supportive social media campaign, #IStandWithAhmed.

Fourteen-year-old Ahmed Mohamed was arrested on Monday after he brought a clock he made at home to school to show his science teacher. After another teacher saw the clock and suspected it was a bomb, he was interrogated for more than an hour by five police officers, then handcuffed and taken to the police station in his home town of Irving, Texas. His arrest sparked outrage against Islamophobia and a supportive social media campaign, #IStandWithAhmed.

Watching a fourteen-year-old kid describe the disappointment of being arrested for his ingenuity rather than rewarded for it is heartbreaking. This event clearly exposes prejudice against brown, Muslim people in the U.S. that is not limited to Irving. Across the U.S., Muslims are the religious group most likely to report experiencing religious discrimination.

But this event exposes another problematic instinct as well: the impulse to resort to law enforcement to solve problems (perceived or real) with kids.

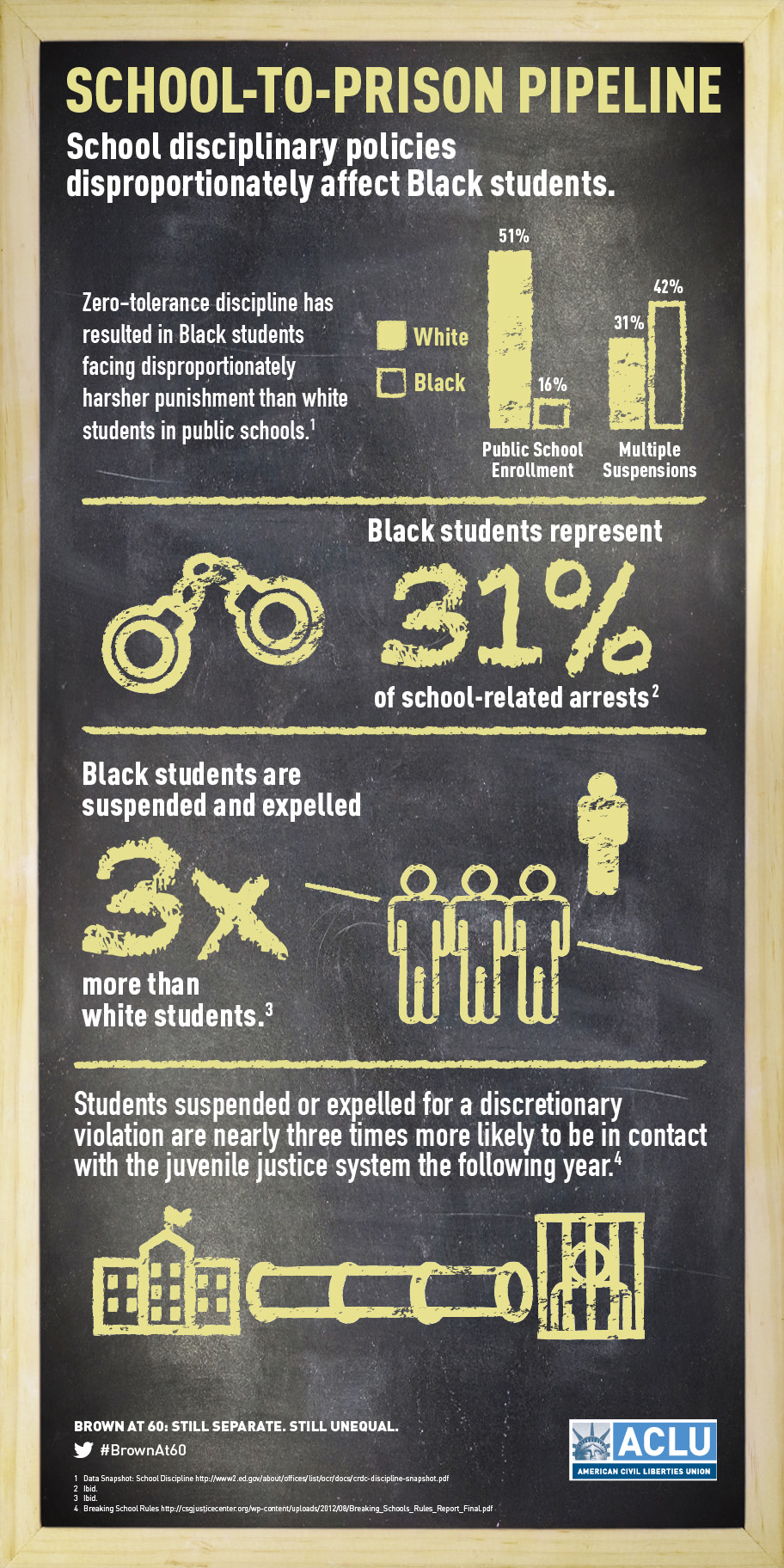

This impulse and the structural changes it has produced has created what is commonly described as the “school-to-prison pipeline,” the funneling of students from schools into the juvenile and adult criminal justice system. The school-to-prison pipeline is built on the notion that (certain) kids in (certain) schools can’t be effectively or safely dealt with by schools, or within classrooms, but must be subject to harsher school-based or criminal justice penalties. The pipeline functions both directly (through law enforcement within schools) and indirectly (through policies that create barriers to school success and contribute to the likelihood of incarceration).

The practice of placing police officers in schools has become increasingly popular in the last twenty years, in part as a response to high profile school shootings. In New York City, the school safety division of the NYPD is larger than Boston’s entire police force. The presence of police officers in schools has led to a dramatic increase in the number of criminal charges brought against students for relatively minor offenses, such as “scuffles, truancy and cursing at teachers.” For example, in Texas alone, 229,000 misdemeanor tickets were issued against students by school-based police officers in 2012. Students typically do not have access to counsel to defend against these tickets, which lead to fines, court fees, and a criminal record, not to mention fostering an adversarial environment in school that alienates kids from their education and vice versa.

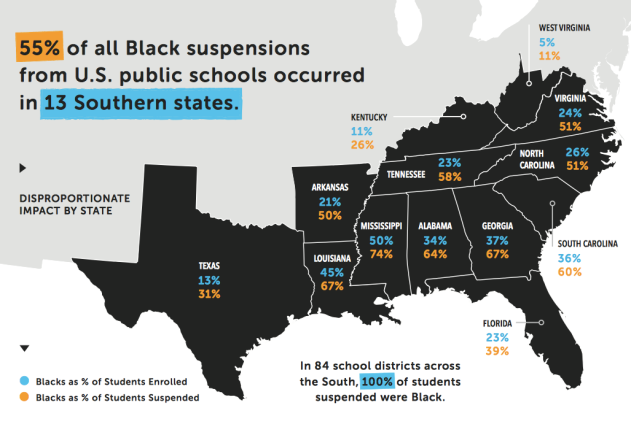

These charges are being brought against students of color at an alarmingly disproportionate rate. African Americans comprise 13.2% of the American population, for example, but make up 31% of school-related arrests. And a full 97% of tickets issued in schools are “discretionary” offenses, meaning that schools have the choice to handle them without involving the criminal justice system. While it’s difficult to say just how biased the application of this discretion is, one useful point of comparison are the offenses punished most commonly by race. One 2002 study found that Black students were most likely to be punished for “being disrespectful and threatening, loitering, and excessive noise” while white students were most often punished for the less subjective offenses of “smoking, leaving school without permission, vandalism, and obscene language.”

In addition to variances in the treatment of individual students, the structural and cultural differences between schools themselves is also illustrative. In New York City, for example, 48% of Black children and 38% of Hispanic children go through metal detectors every day to get into school, while only 14% of white children must do the same. Black and Hispanic children are therefore set up to be criminalized at a much higher rate, a situation that mirrors the disparate police presence in minority neighborhoods.

On top of the growing reliance on the criminal justice system, school-based punishment has gotten harsher – and more racially imbalanced – as well. Rates of suspension and expulsion for Black and Latino children are growing steadily, while the rates for white students are declining slightly. Although suspension and expulsion don’t have the direct relationship with the prison system that the literal policing of school students has, the results of these harsh punishments are perhaps more damaging in the long term. Research shows that students who have been suspended are three times more likely to drop out by the 10th grade than students who have never been suspended. And dropping out triples the likelihood that a person will be incarcerated later in life.

On top of the growing reliance on the criminal justice system, school-based punishment has gotten harsher – and more racially imbalanced – as well. Rates of suspension and expulsion for Black and Latino children are growing steadily, while the rates for white students are declining slightly. Although suspension and expulsion don’t have the direct relationship with the prison system that the literal policing of school students has, the results of these harsh punishments are perhaps more damaging in the long term. Research shows that students who have been suspended are three times more likely to drop out by the 10th grade than students who have never been suspended. And dropping out triples the likelihood that a person will be incarcerated later in life.

By treating students like problems that teachers and administrators can’t solve, schools alienate their kids and create barriers to their successful completion of school – and ultimately to their avoiding the prison system as adults. In the same way that as a nation we have relied increasingly on punishment and warehousing to avoid social problems rather than finding ways to prevent crime, schools too often resort to severe punishment and law enforcement rather than getting to the root of misbehavior. And just as our racially biased policing, prosecution, and sentencing have led to massive disparities in incarceration rates by race, the same biases shape the culture within schools with different racial compositions and the responses to students of different races.

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Baltimore’s mayor, expressed frustration at the approach taken by rioters, accusing them of “trying to tear down what so many have fought for.”

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Baltimore’s mayor, expressed frustration at the approach taken by rioters, accusing them of “trying to tear down what so many have fought for.”

On the one hand, the

On the one hand, the  security prison in the nation, with 6,300 prisoners and 1,800 staff members. It bears a

security prison in the nation, with 6,300 prisoners and 1,800 staff members. It bears a

Getting rid of the screening question altogether (the “

Getting rid of the screening question altogether (the “